Your world is as big as you make it.

I know, for I used to abide

In the narrowest nest in a corner,

My wings pressing close to my side.

But I sighted the distant horizon

Where the skyline encircled the sea

And I throbbed with a burning desire

To travel this immensity.

These are the words of poet Georgia Johnson Douglas and I feel that they perfectly capture the legacy and spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King. When you distill his work down, King essentially fought for the inclusion of those who had been excluded from experiencing their full Americanness by law and custom. Dr. King sought a nation where you could be yourself and not have to sublimate parts of your being so as not to be excluded. Prior to the civil rights movement, a sizable number of Americans from all backgrounds felt they had to pass for someone that they were not in order to avoid the sting of discrimination and denial of opportunity.

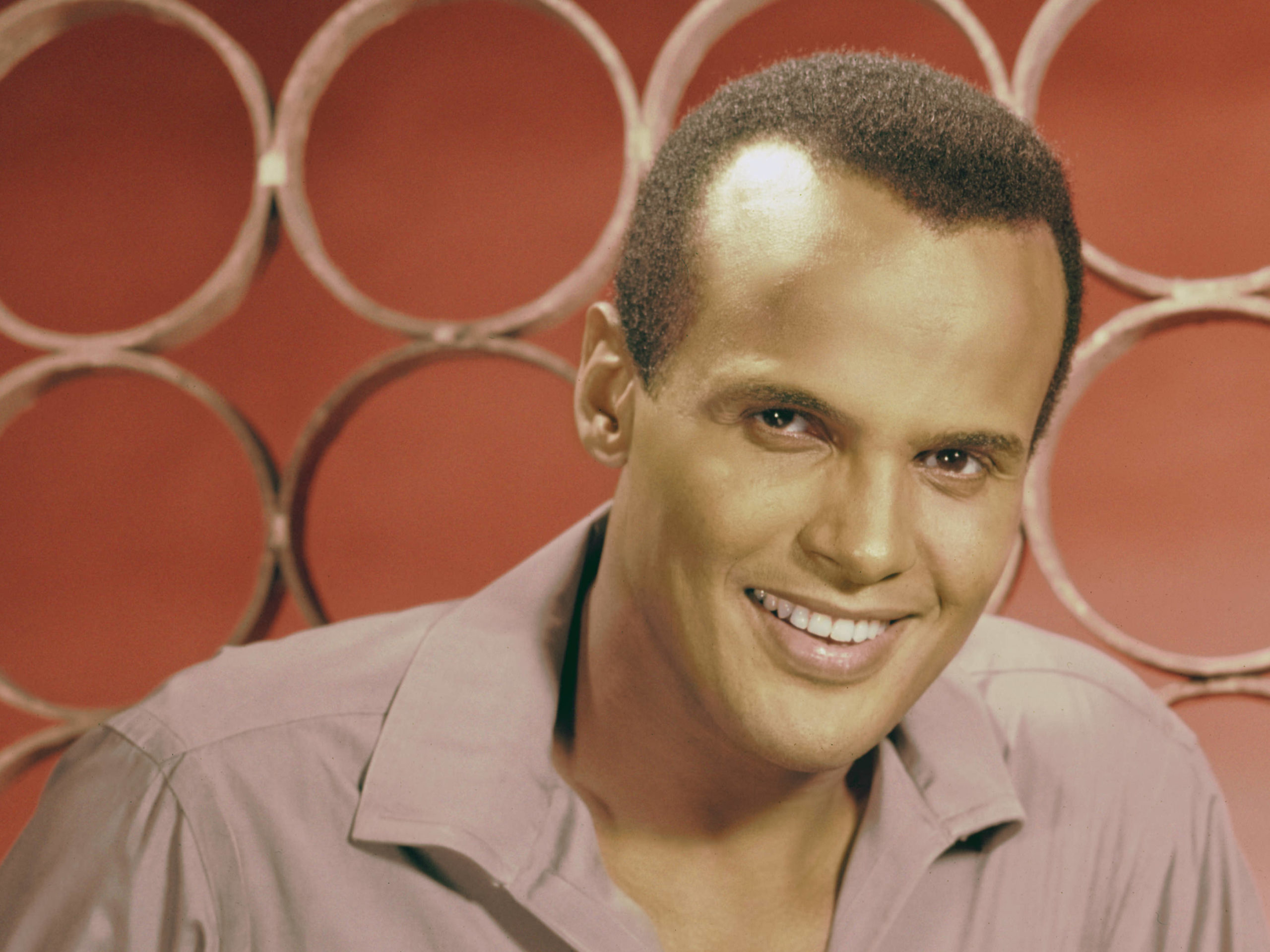

One of the most prominent examples of passing involved African Americans, leading to roughly 2,000 per year passing for white during the first half of the twentieth century. This drastic and painful decision which required erasing one’s history was for some the only way that they felt they could be full Americans. There are so many poignant and tragic stories of families that were forever divided and changed to avoid a life of denial and, to some extent, deprivation. A life where if you were an African American you could not test drive a car, try on clothes, live in certain communities, and could only receive healthcare if an African American doctor or dentist was available. Dr. King, along with so many others, fought to remove these legal barriers. A key milestone in this work was the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Bill, which made discrimination and exclusion based on race or sex, illegal. This, in effect, ended the phenomenon of passing based on race, but did not eradicate it as it pertains to other areas. One such area concerns people with a disability. During the civil rights movement, many of those engaged in the movement were themselves people with a disability. Among several who come to mind are Johnnie Lacy and Harry Belafonte.

Ms. Lacy was diagnosed with polio and Mr. Belafonte with dyslexia. They fought for both civil rights and full inclusion, as they knew that they were intertwined. As we observe MLK Day 2023, let us reflect on how we can enhance the level of inclusion in LISD for our students, their families, and staff so that no one feels they must pass in order to avoid being excluded.

To further illuminate this point as it relates to people with a disability, I have asked my distinguished colleague, Dr. Ken Breslow, to discuss how passing can impact our students and staff with a disability and how all of us can work together to mitigate this. Please see his words below.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 paved the way for two major pieces of civil rights legislation protecting the rights of people with disabilities in the community, in educational settings, and in workplaces: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (“504”), and the Americans with Disabilities Act as Amended (ADAAA). Even though strides have been made, people with disabilities still find themselves underrepresented in employment, education, housing, and transportation. For instance, only 39% of people with disabilities are working, and less who identify as Black and/or Native American (roughly 18%). Compare this to approximately 77% non-disabled who are employed. This data reminds us that the journey to full inclusion is not yet complete.

These numbers also elucidate the reasons that a person with a disability might choose to pass. This can range from pretending to have a disability to hiding one’s disability. For example, President Franklin Roosevelt made an effort to pass as non-disabled to maintain the image of a confident and competent leader. Rarely did the public see him using his wheelchair when he gave speeches. So, the choice for some often comes down to behaving in ways that hide one’s true identity(ies) in order to eliminate stigma, prejudice and discrimination. The stigma felt often becomes internalized which can cause a person to see and refer to themselves in deficit terms. There is often shame. So, to reduce the feeling of stigma, one makes an effort to bypass their identity and to behave in ways which are less pronounced regarding who they are.

What can we do as staff?

All individuals–deaf/hard of hearing and/or disabled, or not–need to feel free from stigma, prejudice, and discrimination. To facilitate that—to make that possible, the first step is to consider bodies and minds as variations rather than deviations. Our thoughts about disabilities lead to the way we act and talk about disabilities.

This is reflected in the degree that instruction honors the entire child, making physical spaces more accessible, and reflecting on what unintentional barriers our policies/rules have on those with disabilities. The more barriers, the more passing. With our changed thoughts and words, we can create a more barrier-free classroom, school, and district, with the goal of disabling the need for passing and allowing all who inhabit this space to travel this immensity.

Leander ISD Chief of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion DeWayne Street and Licensed Specialist in School Psychology Ken Breslow, Ph.D. contributed to this article. For more information on the district’s DEI initiatives, please visit www.leanderisd.org/equitydiversityinclusion.

Sources

Nario-Redmond, M.R., Noel, J.G., & Fern, E. (2013). Redefining Disability, Reimagining the Self: Disability Identification Predicts Self-Esteem and Strategies Responses to Stigma. Self and Society, 12, p. 468-488.

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/odep/research-evaluation/statistics

http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/ip49-education-disability-2018-en.pdf