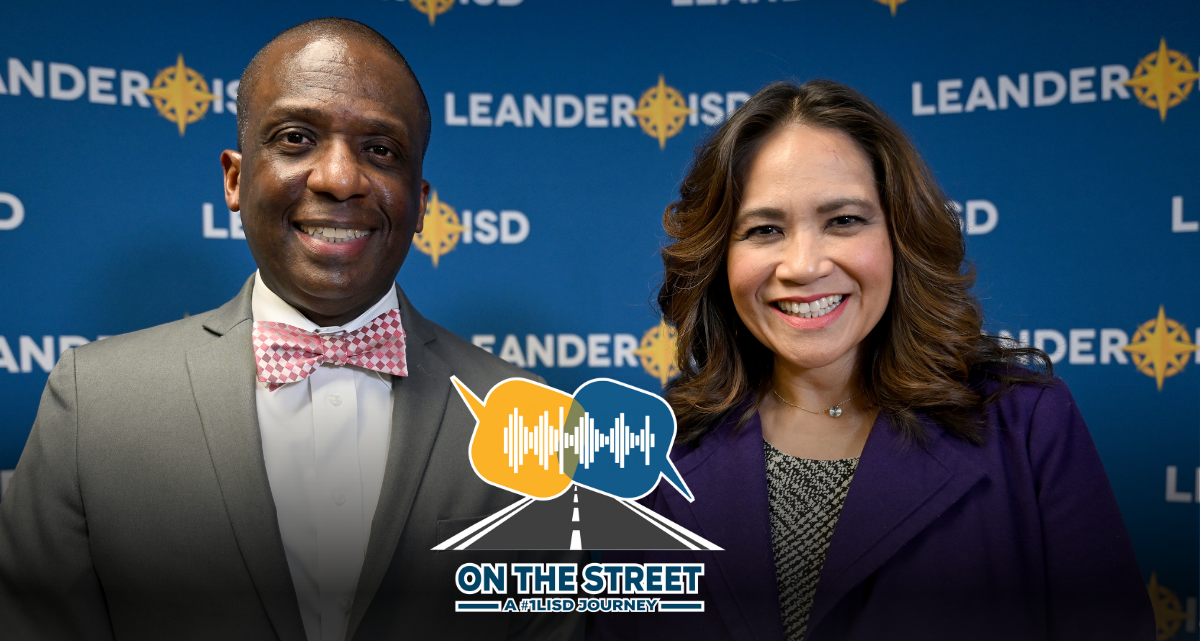

In a special role-reversal episode of the podcast, Chief of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion DeWayne Street served as the guest while Chief Communications Officer Crestina Hardie played host, asking him to speak about his journey and the significance of African-American History Month.

This On the Street: A #1LISD Journey podcast series serves as an opportunity to continue the conversation around educational access and to highlight our efforts around increasing cultural competency for Leander ISD staff. Our work is about bringing people into the conversation.

Episode 5 – African-American History Month with DeWayne Street

Crestina starts by asking DeWayne to share a little bit about himself as a person and as a professional (01:05). Later, Crestina and DeWayne have a conversation centered around:

- Street’s roots in education (03:36)

- Importance of African-American history (10:06)

- Why has African-American history become polarizing? (14:26)

- Putting in the work (16:46)

- Closing (19:00)

Subscribe: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / RSS

Below, you will find a transcript of the episode.

Conversation

Crestina Hardie

Hello, Leander ISD. Welcome to On the Street. My name is Crestina Hardie, Chief Communications Officer, and today, I’m actually guest hosting this awesome little podcast because we’re going to turn the table on this show in order for me to speak in candid conversation with a true host of On the Street, Mr. DeWayne Street, Leander ISD’s Chief of DEI.

So February is African-American History Month, and DeWayne is going to help shed some light, explore and really help us honor the triumph and struggles of the African-American community.

So, DeWayne, I want to tell you from the bottom of my heart, thank you for entrusting me with this episode. It is …

DeWayne Street

No, thank you.

Hardie

It is a great honor to be sitting at this table here with you.

Street

No, it’s an honor to be interviewed by someone who is so professional all the time. So thank you for agreeing to do this.

About Street as a person and a professional

Hardie

Awesome. So let’s get started. So why don’t you tell us a little bit about who you are, both as a person and as a professional?

Street

Happy to. As a person, I grew up in Milwaukee, had the privilege of attending an HBCU after graduating from high school, have had many opportunities over my career, have a tremendous family support network, starting with my wife. I have three amazing sisters. Blessed to still have my parents. Remember all the love and support I got from uncles and aunts when I was coming up. That’s a little bit about me as a person.

Professionally, started my career in 1991. I started teaching high school, teaching African-American history, which was, when I look back on it, probably one of the most transcendent moments of my life. Hands down. I had no idea of the impact that that would have on me for all these years to come and the impact it would have on my family and on the students that I was responsible for.

After leaving the classroom, I had the opportunity to go and be the first African-American coordinator of professional development for a neighboring school district.

So when you talk about African-American history, I think it’s important for people to know that part of that history is still being made right now. And when I think about my career, there have been many opportunities when I’ve been the first African-American to hold that position.

I was the first African-American professional coordinator at that district that I referenced; I was the first African-American education director in Oshkosh Correctional; first African-American male superintendent of schools for DOC; and then also became the first African-American deputy division administrator for employment and training in the Department of Workforce Development in Wisconsin. And then the first person, period, to be named chief equity officer in Round Rock and the first person, period, to be named chief of DEI here.

So when we talk about African-American history, I want people to know it’s living, it’s organic, and it’s not confined to the narrative that a lot of people would have us believe. It’s always about perseverance, acknowledging the things that have happened, but also overcoming challenges not for us, but for those who will come after us.

So I’m very honored to be featured during this episode.

Street’s roots in education

Hardie

I think the one thing that I find so unique about your story is that when you think about our journeys, you had roots in education.

It’s this full circle. And I’m not saying that your circle is complete, but I’m just saying … What a journey, to take you from the classroom and then working in a school district. So, you know, tell us a little bit about, you know, you taught African-American history. What can you tell us if any impact that it had on you?

Street

When I think about how young I was when I first started teaching that course, I was straight out of college. And as I mentioned, I went to an HBCU and I had the privilege of having Dr. Walton, who was a lion in the civil rights movement, was one of my professors for African American history when I was at Alabama State.

But I was not prepared for how teaching that course would challenge me and the assumptions I had about being an African-American. And I’m going to use the terms African-American and Black interchangeably, because to me, when we’re talking about African-American or Black, everyone knows which group we’re talking about. And I know there are some who may want to make an ideological distinction. I just want us to understand that we’re talking about this particular group no matter how we frame it.

So for me, I wasn’t prepared for that level of introspection and challenge that came from teaching the course. I had always seen African-Americans through a very myopic lens, even though I was a student of history. The more I learned about African-American history or Black history, the more I learned about the contributions of our people, the more I learned about the sacrifices that were made.

But then something else happened. When I first started teaching it, I thought that my role was to show people how my students had been devalued and marginalized by this country. But as I matured as a practitioner, the more I learned about it, the more American I felt. And I wanted them to feel that way.

Because no matter which part of U.S. history you look at, African-Americans have always been a part of that, going back to the Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770, Crispus Attucks, all the way up to, you know, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the first Persian Gulf War, African-Americans, and the latest struggles in Afghanistan. African-Americans have been involved in every single war, men and women. And then you think about the contributions that were made. You know, you think about Garrett Morgan and the stoplight; Jan Matzeliger and the shoe-lasting machine; Norbert Rillieux, who revolutionized the refining of sugar. All these contributions – Bessie Coleman – they led me to understand that our place in this country is as secure as anyone else.

We have a unique history, but we can’t allow parts of our history to define our place in this country. And that was a transformation for me. And I was not prepared for that, Crestina. It was overwhelming to some extent, because I saw myself teaching a contrary history to begin with.

But then I evolved to the point where I realized I was just teaching U.S. history from a different perspective.

Hardie

That’s incredible. Do you remember the moment when you acknowledged that?

Street

Yes, I do. I do. I was teaching African-American history my third year and U.S. history at the same time. I had, you know, we were in a seven-period day. So I had, I think I had six courses. And I started to understand that what I was teaching my U.S. history students was remarkably similar to what I was teaching my Black history students.

The only distinction was the perspective. And so I went on this journey – and it was painful – of how do I bring these two together to close this gulf where we’re teaching U.S. history from multiple perspectives, valuing everyone, but also acknowledging the journey of each group. And that was, it was overwhelming at times. And it was a little suffocating, because it was so heavy because I had to shed this notion that my job the first three years was to prove something through history as opposed to just teaching history.

I was out to prove early on a certain view of how I saw the country. That wasn’t my role. History is not about selling the story. It’s about telling the story. And that was part of my evolution.

Hardie

So when you take this defining moment and you move into different career paths, it must have opened your eyes to your approach to everything.

Street

It did. It was transformational for me. And it gave me a sense of confidence that I’ve referenced before that had I not had that experience, I would not have. When I go places, I’m not concerned about being the only Black person in the room, because being an expert in U.S. history and an expert in African-American history, I know that people who look like me have already been there. They’ve already done that. I’m just continuing in a long line of people who simply got it done.

An example that I think crystallizes that was my wife and I were visiting in Quebec City, one of our favorite places. We love Quebec City. And so we were there, and I wanted to go – you know, it has to have a World War II connection …

Hardie

Of course.

Street

So I wanted to go to the place where they held the 1943 Quebec Conference with Roosevelt, Churchill, and I don’t think Stalin was able to get there, but they had this conference at the Le Frontenac Hotel, and so we’re in the hotel and we’re in the elevator, and back then in 1943, they had elevator boys and I saw a picture of all the elevator boys who were at the conference. All of them were African-American.

And even though we know there was segregation and they were only confined to their role, it does not erase the fact that they were there. And so no matter which party history you want to go back to in this country, we were there. And I think it’s important for all students to know that so that when we sit around the table as citizens, we see each other as equals, and more importantly, as equal contributors.

Importance of African-American history

Hardie

That’s beautiful. So when you think about African-American history in 2024, what do you see as some of the most important things that people should know about it?

Street

I believe the most important thing is just how beautiful and how challenging and complex it is. I believe a lot of people, for whatever reason, want to focus on a particular strain of African-American or strand of African-American history because it fits a certain narrative and it fits a certain view that they have.

As a historian, I don’t share that. We know that our history is one of slavery and Jim Crow, but we also know that it’s a history of uplift and survival and perseverance and doing well and getting it done. So there’s a balance that we have to have. We can hold all of it, and all of our students can hold all of it.

But I think we have to look at it through the lens of a mosaic and not through the lens of a telescope. And I think history has been cherry-picked, especially African-American history. There are people who want to cherry-pick parts of it because it drives their personal agenda but is missing the complete story. And by missing the complete story, we are denying to future generations a deeper understanding of our country and of each other.

So I think that’s one of the primary challenges.

Hardie

So when you look at how multilayered this all is, when you have a fuller understanding of all those layers, what’s the benefit of that?

Street

Oh, I think the benefit for African-American students is they see themselves in a complete way that allows them to pursue their dreams with no fear, no reservation.

The story I like to share about that is I still remember watching Lt. Col. Guy Bluford launch into space. He was the first African-American astronaut. I have been a student and just a fanatic of NASA since I was a kid. My mother embarrasses me when people will come over. She still has a picture of me in my NASA astronaut outfit from second grade. No one will ever see that.

Hardie

Oh, come on. You can’t tease us like that.

Street

Well, so I was always a NASA fan. And, you know, but all of the people that I admire, no matter what color they were, were astronauts. And, you know, people like Gus Grissom and Pete Conrad. But when I saw Lt. Col. Bluford, there was a sense of pride in me. It wasn’t so much that he was proving that black people could do it. It was the fact that here’s a person who has worked hard, who has the same skin color I have, and this country is putting him in a position and going to space. That’s what I remember even as a sophomore in high school. And I know the trials and tribulations he had to go through to be the first.

Because to be the first, we have to be the best. And so I appreciated that. But to see him launch a night mission, I was so excited and so filled with pride, and it gave me an opportunity to say, “Oh, if he can do that, I have no excuse about the dreams that I want to chase.”

When I think about Lt. Col. Bluford and what that did for me, I think about all students, no matter who they are, benefiting from seeing the contributions of every citizen and every group, so that as we go on this journey to continue to perfect our union, they have the information they need to see each other as equals. And to me, that’s so important because as Maya Angelou said a long time ago, “only equals make friends.”

And I think it’s very important that we give this generation that gift, you know, of seeing each other as equals, not as marginalized people, not as separate, because we know we all have a history, we all have a story. But when we come together as a collection of citizens, we have to see each other as equals in order for the country to continue to perfect the union and to continue this experiment of democracy.

Why has African-American history become polarizing?

Hardie

So in your opinion, why do you think that African-American history can become so polarizing in recent years? And what can we all do to address this?

Street

I think one of the reasons why it has become so polarizing is because it’s been politicized. History is not political. You know, when you look at the teaching of U.S. history, you look at the teaching of World War II, World War I, the Civil War, we have to just relay the facts. We have to relay – when you look at the social history of our country – let’s relay the facts. But I think African-American history has been hijacked and politicized because there are certain people who want to use the historic suffering of African-Americans to further an agenda. And I don’t think that’s the purpose of history.

History is about showing people what happened, allowing them to construct their own meaning so that we can all go forward together. And I think the U.S. African-American history has been pulled away from that mission by a number of people. And as a historian, I see part of my charge is to restore African-American history to its proper place as a canon of knowledge, because that’s truly what it is. It’s just a canon of knowledge. It’s not to be used to further an end. And I think it has become so politicized.

It stands alone from DEI. It stands alone from other movements, because it is a history that needs to be told. And I also think that part of the reason why it has become so polarizing is that we, who are African-American, we have the responsibility to keep that history alive.

We have the responsibility to continue to learn about it, to share it with those who are coming after us, because by doing that, we’re protecting it from being co-opted or hijacked. We have to be the custodians of the history. Other people can add to it, but we have to be the ones who protect it. And so I think that if more of us understand that, then I think what happens is that it removes it from being politicized or hijacked, or co-opted, and it just becomes another part of U.S. history that can inform our country, just from a different perspective.

Putting in the work

Hardie

When you think about where we are in education and how the massive influx of second-career teachers that we have now who might not have that same perspective, that might more relate to the early version of DeWayne and his teaching and as an educator, what what do you say to them about how to approach these things? Because it is very political.

Street

It is. The thing that I would say is that you have to be willing to put in the work and do the research. You have to be willing to read and challenge the notions that you have. And you have to be willing to ask yourself: “Is the information that I’m collecting only from a singular perspective?” Because I’m a big fan of triangulation. I need to hear from three different sources, three independent sources, before I see validity in it. And I think that’s important for educators to understand.

When I was on my journey to becoming this person as a practitioner, I read everything from multiple sources. I wanted to make sure that the information I was sharing with my students was accurate. And today I say Google-able. Google-able facts, right?

I wanted to make sure that they could look it up and verify it. And for those those educators who are new to the profession, who may not have been classically trained as historians, read, research, challenge yourself, have other people challenge you, and then strip away ideology, strip away worldview, and teach the history in a way where 25 years from now, what you share with your students will still be viable. It will stand the test of time. And I think that’s extremely important.

And I say that to anyone who’s teaching history, no matter which strand of history you’re teaching, it has to be able to stand the test of time. And the things that I share with my students as I matured, those are still facts today. And also, I’m a big fan of African-American history, because history can withstand scrutiny, because it’s all about facts.

And we can interpret the facts the way we want to. That’s the beauty of being an educator. But we have to always share the facts.

Closing

Hardie

DeWayne, this has been amazing. This has just been awesome having this conversation, to be able to speak honestly and earnestly from our hearts about these subjects. Is there anything else that you’d like to share?

Street

Well, first of all, I want to thank you once again for being a guest host. I’m just honored to be a part of LISD and to work with people like you. The only thing that I would say in closing is that we are in African-American History Month, and our history is so beautiful, so dynamic. Let us not miss an opportunity to celebrate all of it, because all of it does matter.

Hardie

All right. Thank you very much, DeWayne.

Street

Thank you.